Frack Me Not, The “eco-art” of Christy Ruppby Ross Rice

Christy Rupp is one of those “eco-artists” you’ve been hearing about. And she’s saying the things you know you need to hear, things that especially resonate now, as we are enduring repeated ecological disasters in search of fossil-fuel energy, apparently willingly trading away natural environments and fresh water to do so.

Painting, photography, and collage are her weapons of choice, and she has no shortage of dragons to slay. As she says, “The collage has always been a favorite medium of mine, because I think it’s inherently amnesiac, you forget what’s under it. And that’s so much about our land policy in America. I grew up around Love Canal, and all of this stuff was: don’t think about it, don’t talk about it, don’t make any waves, it’ll be OK. Until you get sick and die.”

Do you think this (your art) is more of a need for you to express something, or a need for other people to understand something?

“Well, that’s a good question. I think that one of the things that I can do is teach people stuff visually, that we are a visual culture. I’ve always been interested in science, and thought that art and science are an important combination; they used to be taught together, thought of as one thing. So in the sense that I want people to learn or be aware of things, want to expose things…to that extent, I guess I need to do it.”

So is it both?

“I like having a dialogue, it’s not just a one-way conversation.”

A later work apparently required you to become your own corporation, complete with logo. Can you please explain?

“This all started with an interest in bio-piracy, and how companies would go to the rainforest, find a plant, come back to Washington and patent it as a drug, which then made it illegal for native communities to market the stuff. This all came with the concept of Monsanto owning life forms and patenting them, this whole idea that you could control life.”

“Just as kind of a spoof, I decided I would declare the indigenous textiles of Guatemala my personal property…I discovered them! The idea was that because I had discovered them I could claim them, and put logos on them. In so doing, I was making myself a corporation. So I was operating like a one-celled organism, with no acknowledgement that I’m part of a system, just kind of grabbing as much as I could”

One design became the “hand-wringing dish towel,” with the Bush-era color-coded terrorism alert levels sewn into the fabric. “I made a bunch of these, I collected them there, did my logos, wore my own brands like Me First©, or Benefit Package Obliteration©. There were all kinds of funny names we had…”

“I wanted to declare myself as ‘not a human’ partly out of embarrassment, but partly in solidarity with people… like the idea that if you’re too poor to buy things then you’re not part of some global picture.”

Have you gotten irate responses from any of these works?

“You know, people don’t really get conceptual art all that much. And—not that I understand economics—I think that economics is such a fabulous subject to look at as an artist, and to kind of try to explain. Because it is a science, and its got an answer for everything. Rarely does any profession always have an answer for everything.”

What inspired the “Made In U.S.A./Made in China” pieces?

“Well, I was thinking a lot about: what do we produce in this country? Where do we get everything? I got interested in all these invisible workers that make things. And that we’re never really supposed to think about the whole picture of where our goods come from. Noting that everything’s made in China, from eyeglasses to brooms to…families, in some cases, imported from China. So, what are we making? And the only thing I could think of was that our main export product is war.”

“So then I was thinking: OK, I’ll redesign our flag as though we were making flags for the new Middle East that we were going to write our initials all over. And I was noting that in a lot of Islamic flags and design there’s tons of stars and stripes, like our flag. So I got interested in rearranging, doing things in diagonals, changing the fields of color.”

“The idea was that we are remaking the Middle East in our own image, and that we’re really not exporting anything but war, and importing everything else.”

If you don’t mind my asking, how does this work for you commercially? Are you able to sell enough to keep doing this?

“Well, it’s always a struggle, especially with sculpture…it’s really hard. I have taught for years in the CUNY system, sort of recently retired. But I’ve always pretty much had a job.”

Because, I pretty much get the impression you’re not doing this for the money. Not much corporate sponsorship available here…

(Laughs) “I had to become my own corporation to get sponsorship!”

“I’ve always really believed in working very labor-intensively (with) pretty much hand-made stuff, and keeping the overhead down. At some point you realize that you will make more sculpture than the world will ever be able to absorb, and the one thing you actually could do to slow up that pipeline is think more, you know, and really be mindful about what you make.”

“And now I just really love the research process, and I’m really comfortable with things taking a long time to make them. I’ve never really thought selling the work was the way to make the work.”

“Vanishing Bird Collages” in 2008 are a favorite, visually very beautifully rendered…

“Thanks! I tried, based on field accounts, to make everything exactly the right size.”

“(Featured vanishing birds) Parakeets are very social species that would migrate together, settle in a farmers field at night, eat the corn and the grains. So they’d get them with shot pellets. And most birds would leave when they heard the bang sound. But these were so social that they’d flutter around because they would see their flock-mates injured. So they could wipe out a whole flock of them very easily, in a short amount of time. Which is why as a migratory species they were very vulnerable.”

“A lot of animals don’t have this choice that we have, particularly like this spill in the Gulf. They were saying that the fish were leaving the area, but that could be some corporate speak, because (living) things tend to stay where their communities are. They know that whales will swim right through an oil spill if it’s on their way where they need to go.”

The “Extinct Birds Previously Consumed By Humans” exhibit—which recreates skeletons of extinct birds—uses mixed media and includes actual fast-food chicken bones. Please tell us about this, and if you don’t mind my asking, as you don’t seem to be a typical KFC consumer: how did you get the bones?

“Well, a lot of them came from Delaware County, just going to barbeques in the summer, they were all over the place, for the firemen or rescue squad. I kept them in the freezer until I had a lot of them, then I’d boil them for quite awhile, bleach and dry them, by oven and air dry.”

“Of course, for the big birds I needed more bones, so I found a source in Chinatown where you could just buy bones for soup. I started buying them by the pound there. What I did find early in the process was my guidebook, a kid’s book that was really popular: ‘Make Your Own Dinosaur Out Of Chicken Bones’...it shows you step by step how you can do the whole process with household items like Elmer’s Glue, etc….”

How did you capture the extinct species shapes? Is there some imagination and improvisation involved?

“I did my best. First, I started at the Museum of Natural History, and looked at bird skeletons that were available. That was really helpful with the dodo, there was one that’s out in the collection, I photographed that a lot. So wherever I could I would try to see the articulated skeleton of a bird.”

“The way chickens—and even turkeys—are grown, it’s not really fast food, it’s fast-raised food. Their bones are so soft, they have (little) structure to them. It’s kind of like gluing chalk together, you really need an extra layer of archival paper to wrap them.”

What was the response to these pieces?

“What interested me about it was when you see an extinct bird like the dodo, you read that it disappeared in 1690, you think wow, that took so much time, that’s so old, the bird must have been really mature when it died. And then when you think of a chicken, it’s raised from egg to plastic packaging in five and a half or six weeks. And actually from being a live bird to a plastic package is about 20 seconds. (Meanwhile) things are going extinct now every 20 minutes.”

“Also what really got me on this kick—I mean, I’d been interested in the industrial farm complex for a long time, with genetically engineered food and stuff, the whole corporate control of farms. With the avian flu, where they were gassing birds by the billions, basically to provide clean product recall, well I was thinking: those are organisms! They’re animals, and just to kill them all seems like this hideous obliteration of life. Kind of like the (Monsanto) ‘terminator seed,’ really, where you can just take life, and make it again, it’s just dollars and cents.”

Let’s talk about the new works, which are very timely, particularly your “Toxitour” through some oil company-ruined parts of Ecuador…

“I guess I got interested in that question first reading about this idea about oil spills in the Amazon, and reading about how the Amazon is 20% of the world’s fresh water, has so much fresh water it’s still gushing fresh water one mile out into the ocean. Can you imagine if the Hudson River was gushing fresh water a mile out into the ocean?”

“It’s hard to believe that anyone would intentionally pollute that. But actually, (Texaco, now Chevron) did, and it was too much trouble for them (to clean up), and they didn’t think anyone would really notice. Basically, most of this pollution is in the drilling process: like the hydrofracking process, it requires that you send down water and chemicals to get the well to pump; it creates the suction. You have to send down all these chemicals like plasticizers and lubricants, all kinds of things that keep the machinery running, keep it from clogging, just so many chemicals.”

“They have to send all that down, and it comes back up as ‘formation water,’ they call it formed water. In the Amazon, they didn’t bother to treat that water, they would just dig out a big pool, like a swimming pool.”

Could this happen in the US?

“The Clean Water Act of 1977 said you cannot use industry to pollute fresh groundwater. And yet there was this loophole—called the ‘Halliburton loophole’ which was since the terrorist threat came up, back into the 90s—that in the pursuit of domestic energy, you could pollute fresh water, and pass it off to the taxpayers to worry about. And my whole thing is: pollution is not patriotic! If you really loved this country you’d be protecting the water, not dirtying it.”

“(In) Ecuador, they would leave this formation water in the open pits, and hope that this dirty water that was full of oil and chemicals would just evaporate, or get covered up by dead leaves and just disappear! Which it does in the jungle, pretty quickly. But it doesn’t go away, because the water table is so high there that when it floods, those pools go right into the river. And people die, people get cancer, all these cancers that are unheard of. Just because they live in places where the oil company carelessly dumped and never really made an effort to help them.”

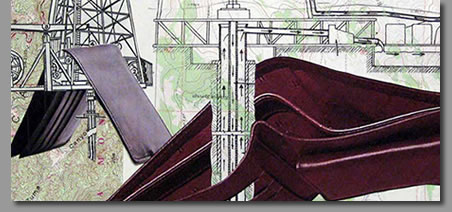

So this segues well into the “Frack Me Not” pieces, discussing the process of hydro-fracturing (“hydrofracking”) to harvest natural gas, particularly in the Marcellus Shale Formation, home to the largest natural gas source in the U.S. sitting under an area from western New York State, extending down into West Virginia. A series of deep-ground explosions and inundation with massive amounts of chemical laden water release the gas. Is the energy worth the wasted water?

“I realized this story is exactly the same. It ends up with the water being bad, people getting sick, you can’t eat the fish anymore, you can’t use your well.”

“These practices take tons of water, way more than used to get petroleum—and they want to put (the water) back. That’s what the loophole says, you can put it into the surface water, you can just discharge, without cleaning it up.”

“It’s unbelievable, really, you might think that oh, they can get away with that in the developing world. It was shocking to me when you heard this expectation, like they can take public water, water that’s being sold, and use it for free…and not even pay the cleanup. Leave people sick and dying for the next twelve generations.”

“The creepy thing about the hydrofracking is the depths of these wells, re-injecting the water back into the aquifer. Well, how do you clean an aquifer? It’s one thing to clean surface water, but an aquifer? You can’t do it.”

Do you think that these pieces can help get the word across about these issues, get the word out more loudly?

“Well, I don’t think that art by itself changes things. But it can create a forum for dialogue, and educate people, and bring people up to speed so they can have opinions. I also think that because art is visual, it has an opportunity to fill in some of the gaps that seem insurmountable because of scientific data and things like that. And that’s when political art gets slammed for being didactic, heavy-handed. That’s just what the art world does with art that’s about content, it has no way to process art that’s really information-driven.”

“There’s a huge movement of ecologically-based art. Check out greenmuseum.org, it’s a clearinghouse, it’s just huge; there are so many artists today, so many ways to work environmentally. It’s all about the dialogue, and the breaking down of artificial boundaries between (artistic) disciplines.”

“This tack I’m on right now is connecting the dots between all these mineral extraction issues and how similar they are all over the globe. Like mountaintop removal has the exact same outcome of polluted water, people unable to leave, people unable to work, dividing communities, making some people pressured to sell, leaving others behind to pick up the pieces. It’s a real issue with indigenous communities, because some of them are interested in the money; it’s hard to exist in a cash economy if you don’t have cash. So when one person, one group, one entity is offered money, it’s extremely divisive. These indigenous communities are so much more complex (than we think.)”

Many think that water issues will be larger and more problematic than energy issues are now, in fact the decision is often becoming a choice between affordable energy and fresh water. We’re there now, aren’t we?

“Well, I think that the time to look at that decision has long passed! The choice has been made to grab the money. It’s just about hiding the costs of cleanup; if you really had to pay to clean these things up, it wouldn’t be profitable. So you have Congress being bought off, making sure there’s nobody in office who really has the power to stop it. The crazy bogus argument about jobs—there are plenty of jobs to be had in green industry.”

So, what’s next for you in terms of projects and installations?

“I’d like to become more educated about energy extraction. I think it’s a really fascinating topic. And just to understand a little bit more and play with our psychological dependence on oil, and why it is we can’t give it up.”

[top]